As Australia celebrates the fortieth anniversary of the Sydney Gay & Lesbian Mardi Gras, a new ABC telemovie is set to stir emotions. Matt Myers takes us back to where it all began, including those original 78er’s.

To many 1978 was a year of fun events. Space Invaders filled video arcades, Grease was the word, and an intriguing new song called Wuthering Heights hit the airwaves. But for the older LGBTIQ community, the year would be so profound that it would change theirs, and the lives of other generations forever.

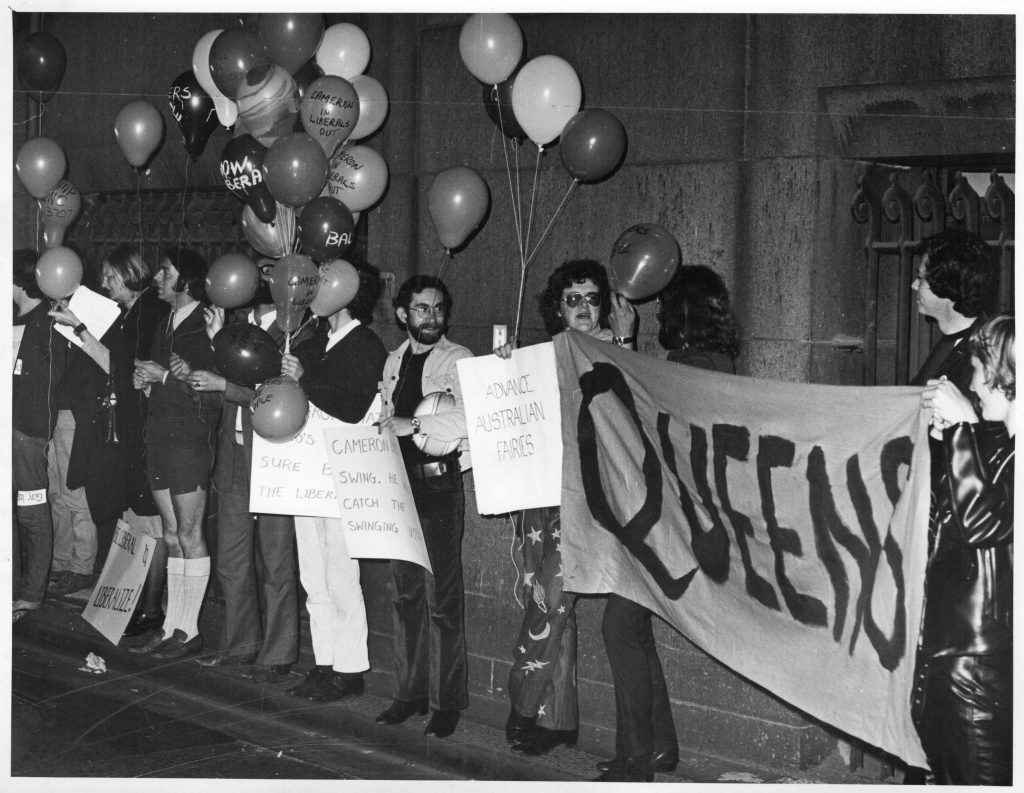

Australia’s current celebration in the wake of the same-sex marriage victory marks the perfect time to spotlight our activist forefathers and foremothers who quite literally paved our way, by that very first Mardi Gras on June 24 1978. But what began as a peaceful and authorised street parade turned ugly with violent clashes spurred on by the New South Wales police. It was undoubtedly Australia’s very own Stonewall moment, and the new ABC telemovie Riot tells the story through those who were there – now affectionately known as the 78er’s.

Directed by Jeffery Walker (Dance Academy: The Movie) and starring Damon Herriman (The Water Diviner), Kate Box (Rake) and Xavier Samuel (Fury), Riot gives a graphic firsthand account of the Australian Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement is in its infancy. Lance Gowland (Herriman) is a spirited and union-bred activist living at the Gay Liberation commune, and is somewhat a mentor to the younger men. He meets Jim Walker (Xavier Samuel) a conservative doctor, and the two begin a relationship.

One of the endearing aspects about Riot is the way it spans the period of 1972 to 1978, focusing on the specific individual stories of those early activists. Other characters in the movie include university students Peter Murphy, played by recent DNA Straight Mate Christian Byers (Friday On My Mind) and Jeremy Fisher, played by Will McDonald (Home and Away). A strong standout character is Marg McMann played by Kate Box and her lover Robyn Plaister, played by Jessica De Gouw (Arrow). While Marg and Lance are born leaders, they also face the difficulties of gay parenting. Marg’s case is particularly poignant when she fights the court system and bigotry towards her being a lesbian. Another common issue for the group includes threats to their employment and living environments.

Historic Sydney groups such as Gay Liberation and CAMP (Campaign Against Moral Persecution) are portrayed with great accuracy. Camp had a unique strategy for media involvement and its two leading founders Peter de Waal and partner Peter ‘Bon’ Bonsall’s home-life had featured on the 1972 edition of ABC’s Chequerboard – a precursor to Australian Story. Tame by today’s standards, the sight of two men kissing and discussing their love for one another was a first for Aussie TV. Now at 79 years of age, Peter de Waal still remembers participating and the effects it had on people.

“Appearing on Chequerboard was most certainly a positive,” says de Waal. “Over the years we’ve had feedback from many people who watched it. One example came about when Bon and I celebrated our fiftieth anniversary in 2016. There was a person at the party who recalled how he was living in the country when the program went to air. He was a teenager feeling very isolated and saw these two people on his television screen providing a very positive image, and from that point on he felt better about himself. The other thing to come out of that program was the acknowledgment of an enduring entity, which began in our house in 1973 and is still around today – the gay and lesbian counseling service. But also, after that program aired Bon lost his job, which wasn’t very positive.”

Indeed, before such positives of today, including last year’s same-sex marriage victory, there were many painful hurdles to be jumped. For starters, homosexuality was still a crime, and when 53 of the 78er’s were arrested, including several beaten by police, there was a public shaming the following day when The Sydney Morning Herald published and outed those taken into custody. Needless to say, jobs were lost and families destroyed. Peter Murphy in particular was targeted in terrible bashing with he labeled a political crime.

“I wasn’t arrested, but I did witness the beatings at the El Alamein fountain,” says de Waal.

“It started off being a very joyous and happy march down Oxford Street and then at the end the police started using their batons. It went from a very joyful evening to the most miserable…well a riot! About fifty or so were arrested and taken to Darlinghurst police station, which at the time was notorious with suspected corruption amongst the police. We stood outside the station chanting to make sure those arrested could hear us. We wanted them to know they had support on the outside. The following week, those who were arrested had to appear in court and the police behaved extraordinary. They even tried to stop the solicitors representing their clients, from entering the police court. There was a huge police presence but also a huge number of the community there to support those who’d been charged.”

To understand the 78er’s character backstories, producers sourced material from documentaries and YouTube interviews, including some conducted by The Sydney Pride History Group. They also met with surviving 78er’s such as De Waal, Peter Murphy, Ron Austin and Robyn Plaister, as well as talking to the children of deceased characters such as Marg McMann and Lance Gowland. The filmmakers also undertook research from Gavin Harris and John Witte who wrote the Mardi Gras publications It Was A Riot! and New Dawn Dawning.

The location shoot naturally featured Oxford Street, Taylor Square and the El Alamein Kings Cross fountain, with additional period facades created at the Sydney Fox Studios. Interestingly, the original CAMP headquarters building in Balmain had been left vacant and proved perfect for recreating the site. Kings Cross was amazingly shut down for filming, where 200 extras linked arms and chanted, “Stop police attacks on gays, women and blacks!” Needless to say, for the real 78er’s visiting the set, there were some strong ‘time tripping’ emotions.

“I visited the set,” says Peter, “It was fascinating, in particular to go back to 1970 when CAMP had its headquarters in Darling Street Balmain. The night I was there they were filming everyone watching the Chequerboard program, that Bon and I were on, and it was quite emotional. I must say I was very happy with my alter-ego Luke Mullins (Holding the Man), and Bon’s as well. They came to our house for a few hours where we chatted about our history. It was a bit surreal particularly seeing Eden Falk (The Great Gatsby) as Bon. When he came to the house he had the familiar beard, but wasn’t wearing the black-rimmed glasses. Then when I saw him on set I was shocked, as he looked so much like Bon!”

Producer Joanna Werner envisioned that each real-life character had a unique personal experience, as she explains.

“Every single one of the people involved in that first Mardi Gras has an individual story, and the events of that night have had an incredible impact on their lives,” she says. “It was important for us not to presume that we were trying to tell everybody’s story.”

But for Werner, it seems, the special on-set atmosphere was felt by all, including those off-camera. “The amazing irony was that a few days before we were going to film, these wonderful, enormous rainbow banners were installed, in support of same sex marriage,” she says. “They were all over our key Mardi Gras re-enactment locations and as much as we wanted those banners to be there, we obviously couldn’t have them in the background of our scenes. The City of Sydney and Mayor, Clover Moore, were wonderfully supportive, and offered to take the banners down at their own expense and put them back up when we’d finished. Having support like that was amazing.”

Since that fateful night in 1978, the Summary Offences Act of NSW was actually repealed the following year, but it took near forty years for official apologies from the NSW Parliament, police and Sydney Morning Herald. So how does such an apology sit with a 78er?

“I think it was a bit tokenistic,” say de Waal. “I was in Parliament the day that the so-called police apology was given, and very few members of the government were present in the chamber. Some of the police from that night are still around, and if they had been there, then perhaps there could have been some sort of conversation, or we could have asked questions. Like how do they feel about things now? Would they still be as eager to arrest us today? Those kinds of things on a personal level would have been more satisfying. It all just seemed a bit abstract.”

By today’s standards the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras is a national icon and a major tourist draw card earning $30 million for the economy. But for those 78er ‘pioneers’ who kick-started the change in law and enhanced our civil rights, it holds a personal significance that we can only imagine. For Peter de Waal, the recent legislation allowing same-sex marriage is somewhat bittersweet. He and partner Bon had planned to marry at their fiftieth anniversary, which fell short of the historic bill. Sadder still is the fact that Bon died five months prior to the passing of the new law. But de Waal still sees the positive. How could he not? After all, he’s an original 78er.

“For the sweet part, it’s a wonderful thing to happen for our community,” he says. “That they can now take the option of a legal contract, because that’s what marriage is, is a wonderful achievement. But I think it’s also important to keep an eye on history, because we can always learn from it. What we did back then certainly galvanized the much smaller LGBTIQ community, and we became focused on working towards equal rights. I’m quite sure of that!”

When Riot premiers this month, it will open many eyes, not just in the LGBTIQ community, but also for the straight. It will start conversations and for the most part, question why this ever happened. Did it need to happen? Most of all, it displays the determination, dignity and humanity of our community and ‘family’ to which we are indebted. Over the film’s closing credits David Bowie sings Heroes, and that really just says it all.

Riot screens during February on ABC1

MARDI GRAS TIMELINE

1978

The first Mardi Gras parade begins peacefully with up to 500 participants, only to be violently interrupted by the NSW police force resulting in arrests, bashings and public outings.

1979

The second Mardi Gras takes place, themed Power in the Darkness, it pays tribute to the previous year’s riot. Participants increase to 3000 with no arrests.

1980

The third Mardi Gras draws a crowd of 5000, moves from the winter to summer and officially becomes the Sydney Gay Mardi Gras.

1981

The Mardi Gras is postponed due to torrential rain.

1982

Mardi Gras makes its first profit of $4000, while the first major after party is held at the Sydney Showgrounds.

1983

The Australia Council provides $6000 in funding, the Sydney City Council places flags along Oxford Street, and the parade (which includes ET and Mary Magdalene) attracts 20,000 people.

1984

Footage form the parade becomes the backdrop for the Cold Chisel Saturday Night video directed by Richard Lowenstein. Mardi Gras makes a profit of $42,000.

1985

Although almost cancelled due to the AIDS crisis, the year’s theme is Fighting For Our Lives.

1987

100,000 spectators attend Mardi Gras, with New Zealanders officially joining the march.

1988

An Aboriginal float leads the parade with indigenous Australian Malcolm Cole dressed as Captain Cook, and Dykes on Bikes join for the first time.

1989

The crowd increases to 200,000.

1990

The first Mardi Gras Fair Day opens.

1991

The parade becomes the largest ever in Australia’s history.

1992

The festival lasts four weeks, making it the largest of its kind in the world.

1993

While the event rejects a $33,000 Playboy condom sponsorship deal, the 500,000 strong event becomes the largest nighttime outdoor parade in the world.

1994

The We Are Family theme includes 137 floats and is watched by 600,000 spectators earning the ABC its highest ratings in history. Kylie Minogue performs at her first after party.

1995

Madonna dedicates her world premiere video Bedtime Stories to the Mardi Gras.

1996

The parade faces criticism over bisexuals and heterosexuals taking part while Telstra becomes the first major corporate sponsor.

1997

Televised coverage moves to the commercial network Channel Ten and special guests include Tina Arena, Chaka Khan and The Village People.

1998

220 original 78er’s are invited to lead the 20th anniversary parade. NSW police also join the march and the first webcast takes place. An estimated $99 million is contributed into the economy.

2000

Mardi Gras is launched by lighting an Olympic-themed ceremonial flame at the Opera House.

2001

This year’s after party includes Chrissie Amphlett performing with 24 lesbian vampires and 24 demonic male dancers.

2002

The event organization goes into receivership with a $500,000 loss, but is saved by community organisations to become New Mardi Gras.

2003

The parade is back on track, making almost $350,000 in profits and former rugby star Ian Roberts is Chief of Parade.

2006

Gaydar provides a $1.5 million sponsorship deal and Brokeback Mountain inspires the marching Brokeback Boys.

2007

Rupert Everett is guest Chief of Parade and Boy George DJs the party.

2008

The 30th Anniversary sees 100 Reverends marching to apologise for Christianity’s past and present treatment of gay people. Olivia Newton-John, Cyndi Lauper and David Campbell all perform.

2009

Olympic gold medalist Matthew Mitcham is Chief of Parade.

2010

George Michael performs at the after party and stays on in Sydney for several weeks!

2011

Intersex is added into the Mardi Gras organisation and there are eight Chiefs of Parade.

2012

The parade includes 10,000 participants and honours Kylie Minogue’s 25 year career and support for the community.

2013

The Australian Armed Forces march for the first time (in uniform) and the famous rainbow crossing appears on Oxford Street.

2014

The People With Disabilities Australia group enter the parade for the first time.

2015

A massive tribute to Freddie Mercury ‘Are Your Ready 4 Freddie?’ wows Darling Harbour.

2017

The City of Sydney’s ‘Say Yes To Love’ float highlights the year’s Same-Sex Marriage Survey vote.

2018

40 Years of Evolution is celebrated. Happy Mardi Gras!